Here is one of my favorite objects. This is one spot in the sky where one can see a large number of stars. With a close look, a variety of star colors can be seen.

Looking up into the sky for fun!

Here is one of my favorite objects. This is one spot in the sky where one can see a large number of stars. With a close look, a variety of star colors can be seen.

(Plain Text Version)

When I step outside around midnight, I am awed by a bright red object high in the Southeastern sky. This is Mars, on its way to a close approach to Earth.

The orbits of the two planets are such that we have a close approach every 26 months. Because our orbits are elongated, some approaches are closer than others. This year’s approach will be closer than normal. In addition, Mars is much higher in the sky (in the Northern Hemisphere) than usual. This allows better views through a telescope.

A little terminology: Earth—Mars Opposition. In a “top view” of the solar system, if you can draw a straight line first through the Sun, next through Earth and then through Mars, we say that Earth and Mars are at opposition (this definition is oversimplified). The closest approach of the two planets occurs within a few days of opposition.

The brightness of Mars is impressive, even without a telescope. Mars will increase in brightness until October 6, 2020. After this date, Mars will begin to fade.

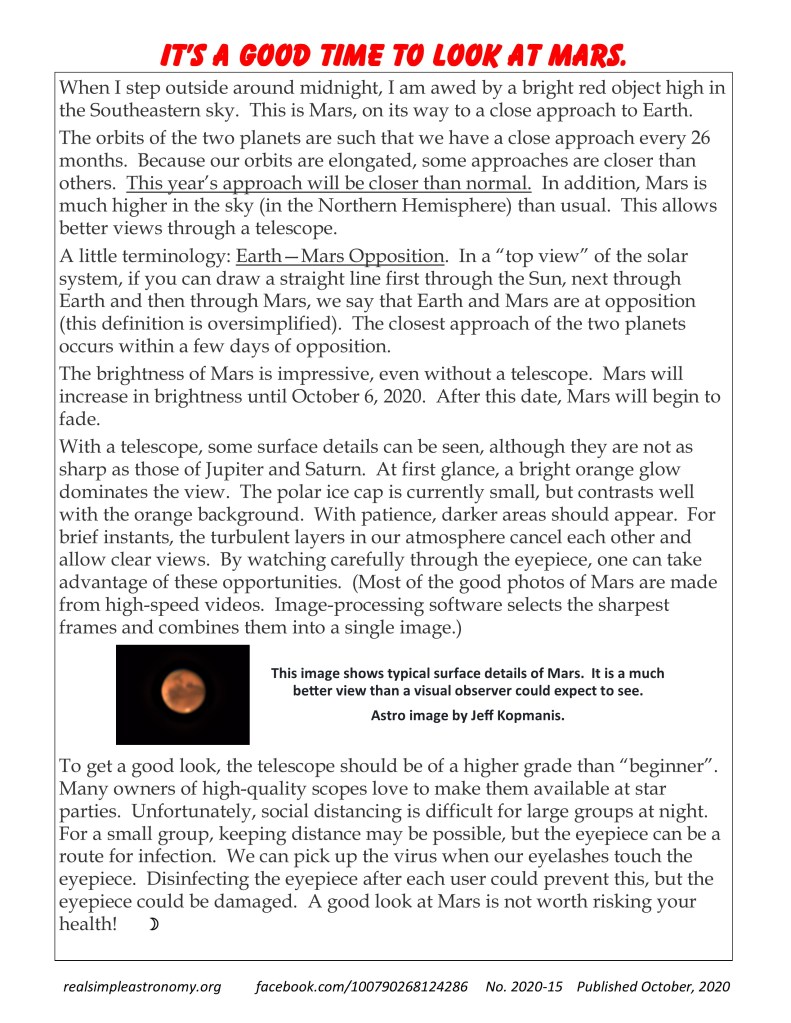

With a telescope, some surface details can be seen, although they are not as sharp as those of Jupiter and Saturn. At first glance, a bright orange glow dominates the view. The polar ice cap is currently small, but contrasts well with the orange background. With patience, darker areas should appear. For brief instants, the turbulent layers in our atmosphere cancel each other and allow clear views. By watching carefully through the eyepiece, one can take advantage of these opportunities. (Most of the good photos of Mars are made from high-speed videos. Image-processing software selects the sharpest frames and combines them into a single image.)

To get a good look, the telescope should be of a higher grade than “beginner”. Many owners of high-quality scopes love to make them available at star parties. Unfortunately, social distancing is difficult for large groups at night. For a small group, keeping distance may be possible, but the eyepiece can be a route for infection. We can pick up the virus when our eyelashes touch the eyepiece. Disinfecting the eyepiece after each user could prevent this, but the eyepiece could be damaged. A good look at Mars is not worth risking your health!

For details, see: https://www.glaac.org/astronomy-at-the-beach-2020/

For details, see: https://www.glaac.org/astronomy-at-the-beach-2020/

(Plain Text Version)

ASTRONOMY AT THE BEACH 2020… WON’T BE AT THE BEACH.

September is the time for a most unique event for those in Southeastern Michigan. A joint effort of 10 astronomy clubs, along with educational institutions and generous sponsors, Astronomy At the Beach offers two evenings of presentations, demonstrations, and observation of the sky.

This is a family-friendly event enjoyed by thousands. Obviously, social distancing would be impossible, so the bad news is that the full event will have to wait for another year.

The good news is that a virtual event will take place. This is good because you can look through telescopes located at a variety of places. (And without waiting in lines!)

But this is especially good news because you can participate regardless of your locale. This year, the event will be on Friday September 25 and Saturday September 26 from 6:00 PM to midnight EDT. For details, see glaac.org, or enter “Astronomy At the Beach” into your search engine.

It would be helpful to study the schedule ahead of time. As with the in-person event, several different activities may happen at the same time, so you need to go where your interest takes you. For my part, I have enjoyed presentations by Brother Guy Consolmagno and David Levy in the past, and look forward to seeing them again.

I hope you enjoy this gathering of people with enthusiasm for science. Who knows—maybe next year Michigan won’t be so far away!

(Plain Text Version)

A Perfect Night Can Be Troublesome

The sky is clear and black, and the Moon is out of sight. I am far away from the city lights. It is a warm night without mosquitoes. The telescope has been working well. Best of all, I don’t have to get up for work tomorrow. It is a perfect night to go out and enjoy the sky.

However, I am already enjoying the skies. I am looking at my new book of Hubble images. Plus, I am a bit tired. And, it can be a big deal to set up the scope. It is so hard to hold it with one hand and open the door with the other hand. And I’ll probably run into problems.

A little voice is scolding me: This is your chance to go out and observe. It may be a long time before you have another one. How about a little effort! What would Herschel say about this? Is this the way Galileo worked? What about the Arabian and Chinese astronomers of long ago? Would they be staying inside?

OK, so what if I am lazy? I don’t have to go out, just because it is clear, dark, warm, Moon-free and mosquito-free.

But the memory of this lost opportunity will haunt me in February, March, and April. Worst of all, I will have to keep an awkward silence the next time we are complaining about the cloudy skies.

In short, I am in turmoil because this is a perfect night. If it were cloudy, cold, Moonlit, or mosquito infested, I wouldn’t feel so bad.

I have an idea. I have a compromise. I need to take the trash out anyway. I’ll just look at the sky for a couple of minutes. I’ll be able to say it was a great night to look at the stars, and that I took advantage of the opportunity. (Maybe I will find that it is cloudy after all.)

So out I go. Wow…the Milky Way is thick tonight…Polaris beckons from the north…My right eye catches the Seven Sisters. Capella is rising in the northeast. Arcturus is fading in the west. I turn to the south, and Jupiter almost hurts my eyes.

I dump the trash and go for the scope. I will get there before the clouds get a chance.

Links:

https://www.amsmeteors.org/meteor-showers/meteor-shower-calendar/

(Plain Text Version)

The Perseid Meteor Shower

The meteors or “shooting stars” which we see at night are solid objects, usually no bigger than a grain of sand, which burn up when they collide with Earth’s atmosphere. Many comets leave trails of these particles in orbits around the Sun. At a particular time of the year, Earth may pass through one of these swarms, producing a “meteor shower”.

Meteor showers happen at all times of the year, but the Perseid shower is very popular in the Northern Hemisphere because it is seen on the warm nights of August. More importantly, it produces a large number of meteors (roughly 60 per hour). The Perseids reach their maximum on the night of August 11-12, but they are also seen for a couple of weeks before and after that time.

The “right” way to observe a meteor shower is to simply lay back on a lounge chair, and watch a particular section of the sky (see links for details). Before your eyes get dark-adapted, you may think that nothing is happening. After a few minutes, your vision will be improved. It takes about 40 minutes to achieve full dark adaptation. This can be lost very quickly if you look at a white light!

For those who don’t want to go to all of this trouble, the peak night of the Perseids is the time to watch. If one goes outside and watches for 10 minutes, one or two shooting stars will likely be seen.

The brightness of the meteors ranges from extremely dim to that of a bright star. They move very fast. Sometimes, the event will look like a gray thread which very briefly flashes and disappears.

This year, the Perseids share the sky with the waning crescent Moon, which will hide the dimmer meteors. Next year, the Moon will not interfere with the Perseids.

I have included some links with details. One link is for a live webcast from the Lowell Observatory in Arizona. They will use an “all-sky” camera to show the meteors. I have never seen this, but I will check it out if it is cloudy at my home.

Here is a link with instructions for locating comet NEOWISE:

https://skyandtelescope.org/press-releases/new-bright-visitor-comet-neowise/

Here is the link to the Astronomy magazine article:

https://astronomy.com/news/2020/07/comet-c2020-f3-neowise-springs-a-naked-eye-surprise

(Plain Text Version)

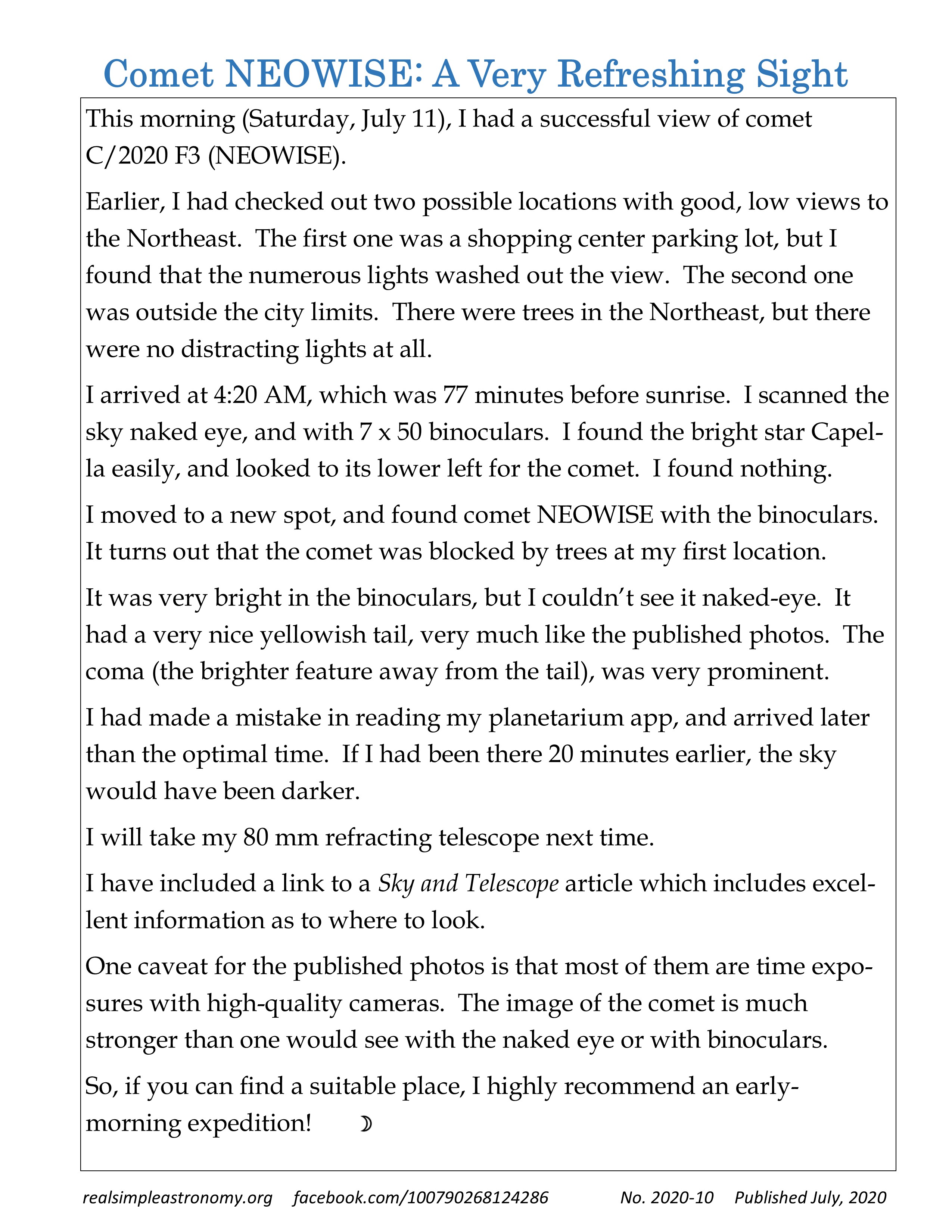

We are finally in the right position to greet a visitor from the dark, icy fringes of the solar system. Comet C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE) has survived its close encounter with the Sun, and is now approaching our planet. We have countless reports that it is great to observe with a telescope, binoculars, or the naked eye.

Rather than retelling the story, I recommend the link to an article from Astronomy magazine.

Morning Comet…Invisible…Evening Comet…Departure

Right now, NEOWISE is visible just above the horizon in the morning twilight. You will need a site with a clear view of the horizon to the Northeast. The bright yellow star, Capella, will be just above the comet. The best time to look is a bit tricky. Since it is near the Sun, it won’t rise until about 2 hours before sunrise. It will get higher with time, but the sky will be getting brighter. So, somewhere in the middle is the best time to catch this object. I would recommend starting about 1-1/2 hours before sunrise, and checking the area every 5 minutes.

After a few more days NEOWISE won’t be visible because it will rise with the Sun. Around July 15, it will begin to be visible in the Northwest after sunset. It’s setting time will be later each day, making observation much more easy. But, there is another catch…the comet will start moving away from us, so it will start losing brightness and detail.

Safety First.

In the morning, one must be careful not to look at the Sun through a telescope or binoculars, even briefly. One way to avoid this would be to set an alarm for 20 minutes before sunrise. This would be the signal to stop observing (the sky would be too bright anyway).

Happy comet hunting!

Here are links to more information on the SSE system:

https://www.celestron.com/pages/starsense-explorer-technology

https://www.celestron.com/collections/starsense-explorer-smartphone-app-enabled-telescopes

(Plain Text Version)

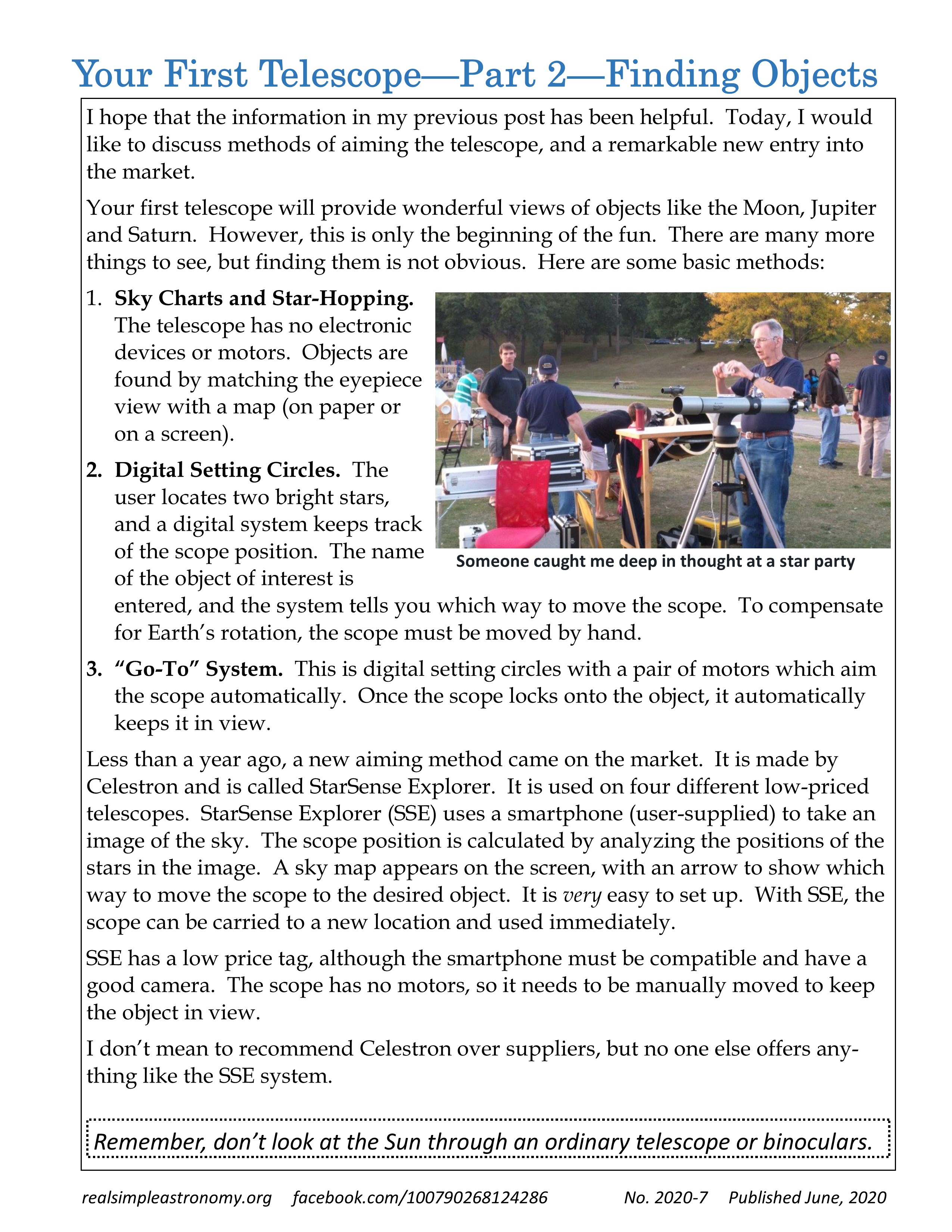

I hope that the information in my previous post has been helpful. Today, I would like to discuss methods of aiming the telescope, and a remarkable new entry into the market.

Your first telescope will provide wonderful views of objects like the Moon, Jupiter and Saturn. However, this is only the beginning of the fun. There are many more things to see, but finding them is not obvious. Here are some basic methods:

1. Sky Charts and Star-Hopping. The telescope has no electronic devices or motors. Objects are found by matching the eyepiece view with a map (on paper or on a screen).

2. Digital Setting Circles. The user locates two bright stars, and a digital system keeps track of the scope position. The name of the object of interest is entered, and the system tells you which way to move the scope. To compensate for Earth’s rotation, the scope must be moved by hand.

3. “Go-To” System. This is digital setting circles with a pair of motors which aim the scope automatically. Once the scope locks onto the object, it automatically keeps it in view.

Less than a year ago, a new aiming method came on the market. It is made by Celestron and is called StarSense Explorer. It is used on four different low-priced telescopes. StarSense Explorer (SSE) uses a smartphone (user-supplied) to take an image of the sky. The scope position is calculated by analyzing the positions of the stars in the image. A sky map appears on the screen, with an arrow to show which way to move the scope to the desired object. It is very easy to set up. With SSE, the scope can be carried to a new location and used immediately.

SSE has a low price tag, although the smartphone must be compatible and have a good camera. The scope has no motors, so it needs to be manually moved to keep the object in view.

I don’t mean to recommend Celestron over suppliers, but no one else offers anything like the SSE system.

Remember, don’t look at the Sun through an ordinary telescope or binoculars.